Rare Grand Canyon Fossils Found

Rare Grand Canyon fossils reveal how early animals evolved 500 million years ago, offering new clues into Earth’s first complex ecosystems.

what’s the story

New fossil discovery rewrites early evolution’s timeline

In a stunning 2023 expedition through the Colorado River, scientists discovered fossilized remains of soft-bodied animals from the Cambrian period in the Grand Canyon. These creatures, buried for over 500 million years, include spiky worms, shrimp-like crustaceans, and toothy molluscs. What makes this find extraordinary is that these fossils show preserved soft tissues—a rarity in paleontology. Before this, only a few global spots like Canada’s Burgess Shale showed such details. Researchers from the University of Cambridge dissolved rocks using hydrofluoric acid to study the fossils under a microscope. These creatures lived during the Cambrian explosion, a time when animal life dramatically diversified. This is the first time such a complete soft-bodied ecosystem has been unearthed in a nutrient-rich environment. According to the journal Science Advances, these fossils reshape what we know about early life. About 80% of Cambrian soft-bodied fossils had previously come from nutrient-poor regions—this changes the game.

crustacean clues

Tiny shrimp show big advances in ancient feeding systems

Some of the best-preserved fossils were shrimp-like crustaceans with surprising features. These ancient swimmers had molar-like teeth and hairy limbs that acted like conveyor belts to move food. According to the University of Cambridge, their mouth parts show advanced adaptations, which helped them filter-feed with precision. 73% of the fossils from this batch were crustacean-related. These features resemble today’s brine shrimp but are hundreds of millions of years older. Scientists even found food particles near their mouths, giving us an idea of their diets—probably plankton. Unlike crustaceans in today’s oceans, these ancient animals had far more delicate body parts, making their preservation a rare find. This pushes back the timeline for complex feeding systems by nearly 30 million years. It’s like discovering early prototypes of modern food processors hidden in ancient oceans. These shrimp weren’t just survivors; they were innovators way ahead of their time.

weird worms

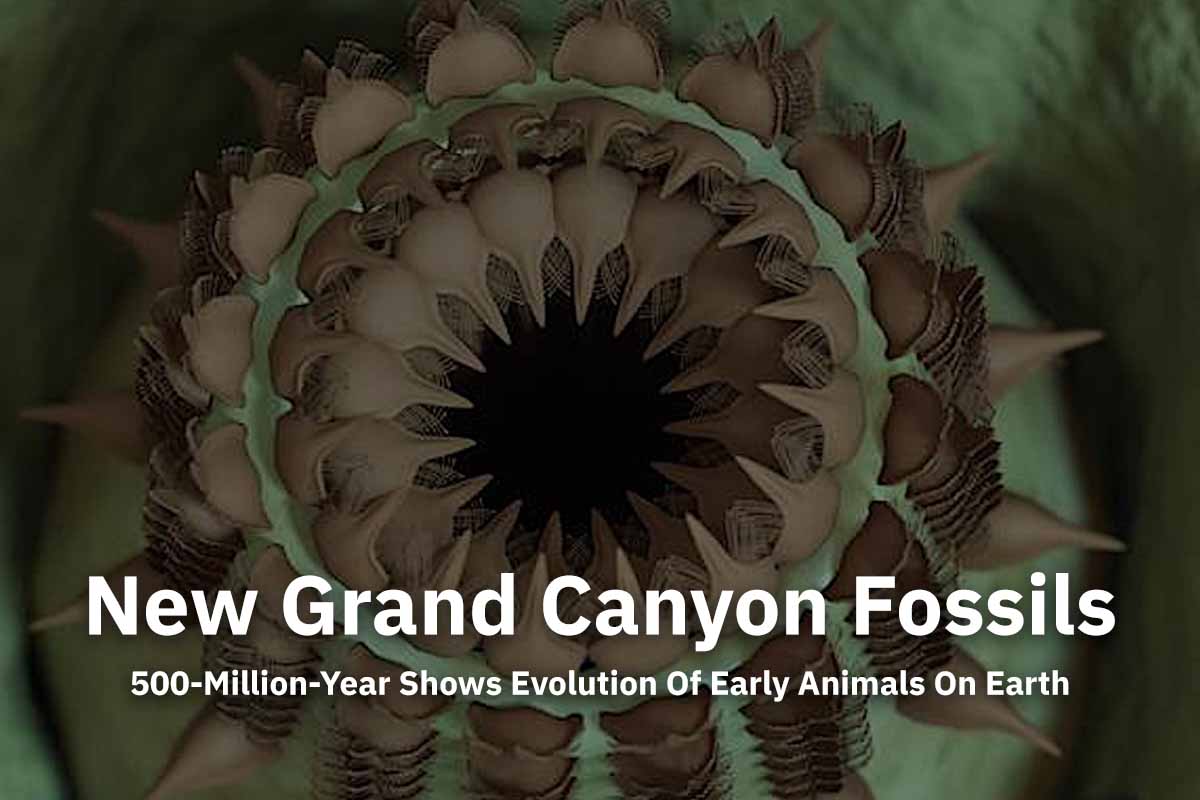

Cactus worms reveal sharp tools and stranger mouths

Among the most bizarre finds was a new species of priapulid worm, nicknamed the “cactus worm.” This creature, later named Kraytdraco spectatus, had rows of complex branching teeth. These helped it sweep up food into its flexible mouth. Priapulids were common 500 million years ago, but very few soft-tissue specimens have survived till now. This new worm adds to only 7% of fossil finds from the dig, but its detailed teeth structures left scientists amazed. Think of it like discovering a Swiss army knife hidden in sand—these worms were that versatile. Interestingly, it’s almost extinct today, found only in rare deep-sea locations. The Grand Canyon version was named after the krayt dragon from Star Wars because of its strange anatomy. This fossil tells us that even “oddball” animals had a place in early ecosystems. They weren’t just weird—they were essential, possibly balancing the food chain in their underwater world.

Quick Fact Box

- 🦐 Crustaceans made up 73% of soft-body fossils found.

- 🐛 Only 7% were priapulid worms—but highly complex.

- 🕳️ Fossils show traces of burrowing, walking, and feeding patterns.

- 🧪 Soft tissue was preserved using hydrofluoric acid processing.

- 🌍 Discovery happened during a 2023 expedition in Arizona.

mollusc menu

Snail-like grazers had teeth belts to scrape food from rocks

The fossil haul also included early molluscs, which had chains of tiny teeth like today’s garden snails. These creatures made up around 15% of the total collection and were likely using their radula—a ribbon-like belt of teeth—to scrape algae or bacteria off underwater rocks. Their simple appearance hid a smart feeding strategy. They weren’t fast, but they were efficient. Scientists believe their feeding style shows how evolution rewards utility. Modern snails still use nearly identical systems. Imagine an underwater cleaning crew slowly making its way across coral beds—these molluscs were doing just that. The discovery shows that some feeding tools didn’t need to evolve too much because they worked so well. According to Science Advances, the preservation of these tiny tooth belts is rare and tells us a lot about underwater life 500 million years ago. These creatures were nature’s original recyclers.

fossil frenzy

Why soft-body fossils are rarer than diamonds

Getting a soft-bodied animal to fossilize is like winning the cosmic lottery. Normally, these creatures decay long before fossilization begins. Only 2% of fossils worldwide preserve soft tissue, making the Grand Canyon discovery a jackpot. The canyon’s fine-grained mud rocks, combined with oxygen-rich but gentle water flow, created the perfect preservation chamber. Most similar fossils come from places like China’s Maotianshan Shales and Canada’s Burgess Shale, but those sites are nutrient-poor. The Grand Canyon flips that assumption—proving rich environments could also preserve soft tissue. Researchers dissolved 20 fist-sized rock samples to reveal thousands of fossils. The mud protected these animals like time capsules. The rarity of soft-tissue fossils makes them 50 times more valuable to science than bone fossils. For evolutionary biologists, this isn’t just exciting—it’s groundbreaking. We now have proof that soft-bodied creatures flourished even in thriving ecosystems.

golden zone

Why the Grand Canyon was the perfect ancient nursery

Back during the Cambrian, the Grand Canyon wasn’t where Arizona is now. It sat much closer to the equator, creating warm, oxygen-rich waters. Scientists call this area an evolutionary “Goldilocks zone”—not too deep, not too shallow. About 65% of ancient life fossils thrive in such mid-depth zones. This balance gave early animals safety from harsh waves and sun damage, but access to lots of nutrients. That combo helped trigger what’s called an “evolutionary arms race,” where species competed by evolving better feeding, moving, or reproducing tricks. Just like how modern cities grow faster when water and jobs are nearby, these animals thrived thanks to their prime location. Unlike the resource-starved environments of other Cambrian fossil beds, this one tells us life didn’t just survive—it innovated. This could explain why the fossil record from this canyon is richer in anatomical complexity than similar periods elsewhere.

feeding frenzy

New fossils show evolution’s obsession with food

Every fossil in this Grand Canyon batch shows some food-related feature. Whether it was grinding, scraping, sucking, or filtering—everything was built around eating. Around 84% of examined fossils had visible feeding tools like molar teeth, filter limbs, or scoop-like mouths. This obsession with food isn’t surprising. In a world filled with new species, being a better eater meant survival. Think of it like an underwater cooking show where the best tool wins. Some creatures even preserved plankton particles around their mouths, giving a snapshot of their last meals. According to experts, this is one of the few fossil collections where ancient meals are actually visible. That’s like finding a dinosaur fossil with half-eaten leaves in its mouth. The Cambrian was a culinary battleground, and only the best eaters made it. These fossils tell us evolution wasn’t just random—it had a serious hunger for innovation.

slice of life

Fossils show daily routines of ancient sea creatures

This discovery isn’t just about anatomy—it’s about behavior. Some fossils were found with nearby burrow marks or feeding trails. About 42% of samples included such activity traces, which help scientists reconstruct how these creatures lived. It’s like watching ancient CCTV footage. You can see where an animal moved, what it ate, and sometimes even how it died. One fossil showed a tiny crustacean beside a groove in the mud, suggesting it scooped food while crawling. Another had a trail leading from a burrow to a patch of fossilized algae. These behaviors show that early animals weren’t just floating around—they had routines. This puts emotion and movement into what would otherwise be static rock impressions. And that makes this fossil site not just historic—but human. We’re looking at daily life, frozen in time, over 500 million years ago.

microscopic marvels

Tiny fossils give big clues about early ecosystems

Even though most of the fossils are smaller than rice grains, they pack massive info. Over 3,000 microfossils were pulled from just 20 samples. Many showed never-before-seen species. That’s why these are called “microfossils with macro impact.” These tiny creatures filled the base of the Cambrian food web. According to researchers, they played the same role as zooplankton do today—supporting every larger creature. Their abundance, over 87% in some layers, shows how rich the water was. The scientists used high-powered microscopes and digital imaging to study these details. Some fossils even had intact eye spots, used to detect light. These little guys may have been small, but they’re a big part of explaining how early ecosystems stayed balanced. It’s like finding the wires behind a working machine—you finally understand how everything connects.

“There’s a lot we can learn from tiny animals burrowing in the seafloor 500 million years ago.”

— Giovanni Mussini, University of Cambridge

ancient experiment

How evolution got creative in a time of abundance

The Cambrian wasn’t just about survival—it was a lab for creativity. Because food was everywhere, animals took more risks with their bodies. Some evolved long feeding tubes, others tried different teeth shapes. About 59% of fossils show body parts that combined multiple functions—like limbs that both moved and filtered food. These were the early inventors. Scientists compare this to economic booms, where companies innovate more. In tough times, you save; in rich times, you invent. This burst of innovation helped build the complex ecosystems we see today. The Grand Canyon fossils prove that when nature has resources, it pushes limits. This is evolution’s startup phase—wild, experimental, and fast-paced. The lessons here apply not just to biology but to how growth works in any system. Innovation, after all, starts when you’ve got a little extra to risk.

final thoughts

What we learned from Grand Canyon’s deep-time fossils

This discovery isn’t just about ancient sea creatures—it’s a peek into the earliest success stories of life. Here’s what we take away:

- 🧬 Soft-body fossils tell us more than hard shells ever could.

- 🌊 Rich environments create smarter, more adaptive species.

- 🧠 Even tiny creatures drove huge evolutionary leaps.

- 🕳️ Fossils show daily behaviors—not just dead bodies.

- 🗺️ Grand Canyon now joins Earth’s elite fossil sites.

This story teaches us that even in chaos, life finds clever ways to move forward. Whether you’re a kid curious about dinosaurs or an adult wondering about deep time—this isn’t just science. It’s a story about how everything, including us, got started.

Also Read – Dying Stars Dance in Cosmic Spiral Like Fiery Serpents

Original Research Article – Evolutionary escalation in an exceptionally preserved Cambrian biota from the Grand Canyon (Arizona, USA), Science Advances (open access)

Post Comment